In an era dominated by the colossal power of nuclear weaponry, the U.S. Navy flirted with the idea of transforming the iconic Iowa-class battleships into the ultimate nuclear artillery platforms.

In the waning years of the 1950s, amidst Cold War tensions and an arms race that saw no parallel, the Navy conceived an audacious plan: equip its most formidable warships with nuclear ordnance.

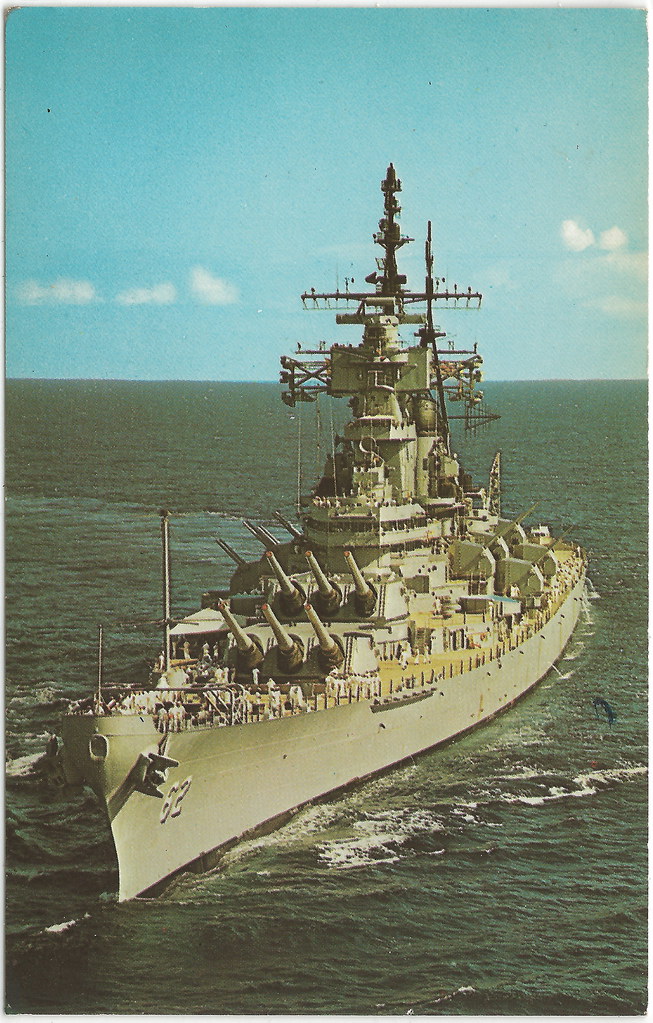

These seafaring behemoths, which reigned supreme during World War II with their massive 16-inch guns, faced the threat of obsolescence in the new age of guided missiles and long-range bombers.

The military strategists of the day proposed two visionary upgrades that would have maintained the relevance of the Iowa-class in the nuclear era.

The first proposal sought to overhaul the battleships completely, stripping them of their iconic guns and refitting them as “guided missile battleships.”

These revamped vessels would carry four Regulus II cruise missiles, each capable of devastating a city over a thousand miles away with a nuclear payload surpassing the Hiroshima bomb’s power by more than a hundredfold.

However, this transformation was fraught with inefficiencies, not least of which was the fact that an Air Force bomber could accomplish the same mission with less crew and more flexibility.

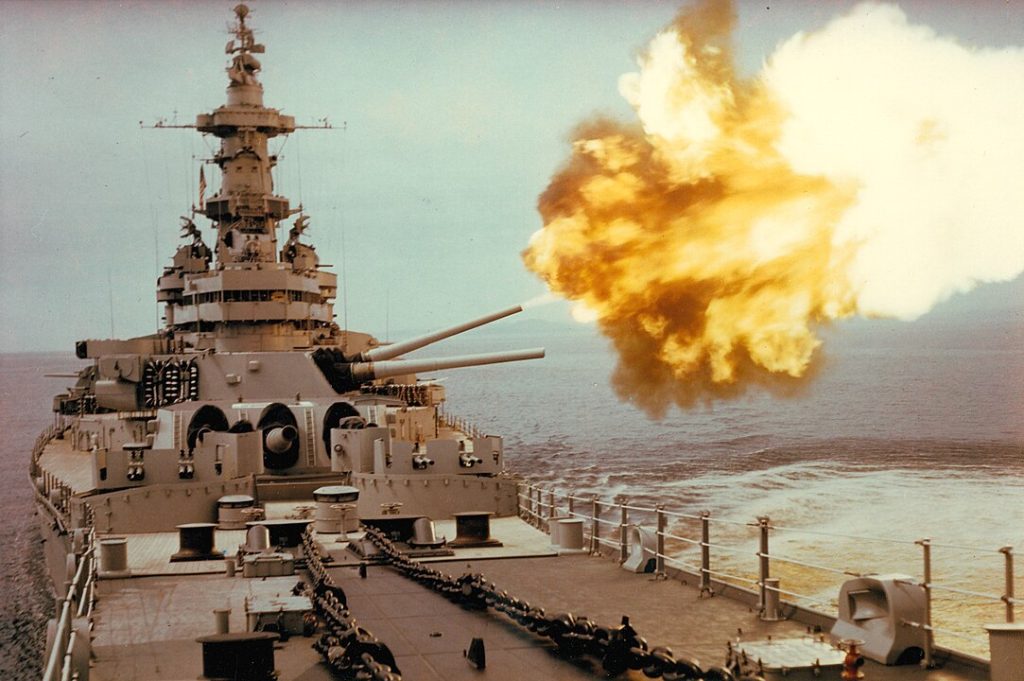

The second, more dramatic proposal was to augment the existing firepower with Mk 23 “Katie” nuclear shells. These rounds, developed in 1953, boasted an estimated yield of 15 to 20 kilotons and were designed to be fired from the Iowa-class’s main armament, transforming them into the most formidable nuclear artillery ever conceived.

The USS Iowa (BB-61), USS New Jersey (BB-62), and USS Wisconsin (BB-64) underwent modifications to their Turret II magazines to accommodate these shells, capable of delivering a combined yield of 135-180 kilotons.

“Each ship would have ten Katie projectiles and nine practice shells. This would give the navy the biggest and most powerful nuclear artillery in the world,” reported Brent Eastwood, underscoring the staggering might that the Iowa-class would have wielded.

Yet, for all their potential, these nuclear projectiles were never used in combat. By October 1962, the Navy had withdrawn them from service. Only one practice shell was fired during a test in 1957 by the USS Wisconsin, and another was expended for the peaceful Project Plowshare.

The secrecy shrouding these weapons was characteristic of the era’s military policies. The Navy’s stance of neither confirming nor denying the presence of nuclear weapons aboard its vessels only added to the mystique of these battleships and the potent capabilities they nearly possessed.

As Fred Kaplan elucidates in his book “The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear War,” the Katie shells were integral to a wider military strategy, reflecting the era’s belief that a nuclear war could be “won.”

Kaplan states, “All of these options envision the bomb as a weapon of war, writ large. This vision has been enshrined in the American military’s doctrines, drills, and exercises from the onset of the nuclear era through all its phases.”

Today, a silent testimony to the might-have-been resides at the National Atomic Museum in Albuquerque, New Mexico—an inert Mk 23 shell body, a relic of a time when sea power could have taken a nuclear turn.

Relevant articles:

– The Navy’s Iowa-Class Could Have Been a ‘Nuclear’ Bomber Battleship, The National Interest

– The Navy’s Iowa-Class Could Have Been a ‘Nuclear’ Bomber Battleship, nationalinterest.org

– Iowa-Class Battleships: Could They Have Fired Nuclear Bomb ‘Shells’?, The National Interest