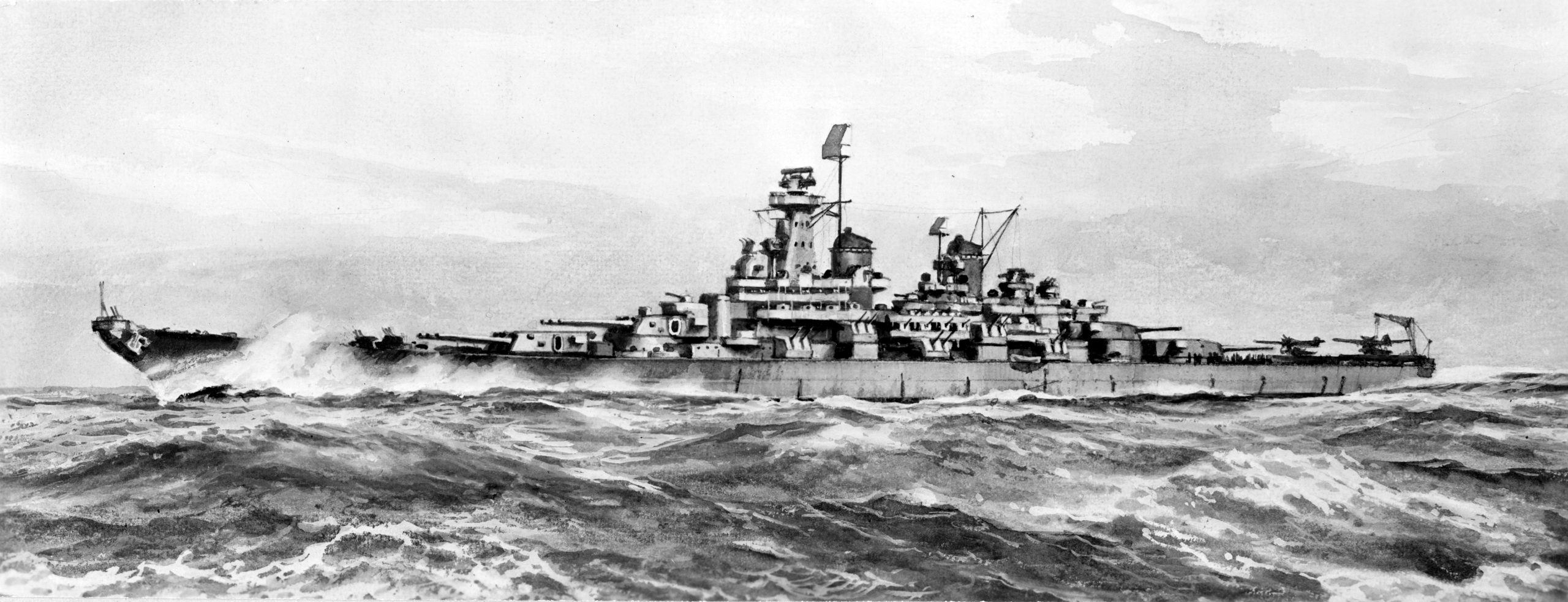

In the tumultuous early 1940s, as World War II raged across the globe, the United States Navy found itself at a pivotal crossroads between tradition and innovation. With the shadows of war looming large and the Japanese Yamato-class battleships threatening dominance in the Pacific, the U.S. Navy embarked on an ambitious project to build the most heavily armed battleships ever designed—the Montana class. These leviathans of the sea represented the zenith of battleship design, with unmatched firepower and armor, yet they were destined to remain on the drawing boards and fade into the annals of history without ever cutting through the waves.

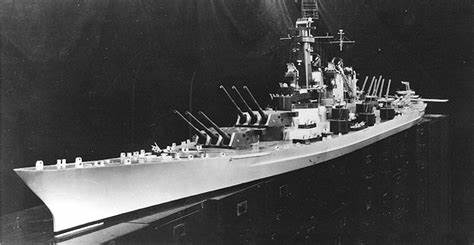

The Montana class battleships, conceived under the auspices of the 1940 “Two Ocean Navy” building program and funded in Fiscal Year 1941, were the last battleships ordered by the U.S. Navy. They boasted an intended standard displacement of 60,500 tons, nearly a third larger than their predecessors, the Iowa class. The Montanas were designed to carry a daunting array of twelve 16″/50 caliber guns, three more than the Iowas, and were to be the only new World War II era U.S. battleships adequately armored against guns of the same caliber as their own.

“Completion of the Montana class would have given the late 1940s U.S. Navy a total of seventeen new battleships, a considerable advantage over any other nation,” indicating the immense power projection these vessels could have wielded. They were envisioned as true behemoths, with dimensions of 921 feet in length and a maximum beam of 121 feet, powered by 172,000 horsepower steam turbines for a maximum speed of 28 knots. Their armor and secondary batteries of twenty 5″/54 guns in ten twin mountings were no less impressive, preparing them to dominate in an era where big gunships ruled the seas.

However, the shifting tides of war and technological advancement did not favor these goliaths. In May 1942, before any of their keels had been laid, the construction of the Montanas was suspended, and by July 1943, with the strategic importance of battleships in decline, their construction was canceled. The decision to scrap the Montana class reflected a broader shift in naval warfare’s fundamental nature, acknowledging the rise of air power and the aircraft carrier as the new arbiters of naval supremacy.

The Battle of Midway fought in 1942, emphasized the pivotal role of aircraft carriers, reshaping the naval doctrine that would guide the U.S. Navy through the remainder of the war and beyond. The necessity for more aircraft carriers, amphibious and anti-submarine vessels, and the limitations imposed by the existing Panama Canal locks rendered the Montanas a mismatch for the new direction of naval engagements. They simply could not compete with the versatility and strike capability offered by carriers.

The potential psychological boost to morale following the Pearl Harbor attack, that a Montana class super battleship could have provided, was recognized but ultimately deemed too costly in the face of more pressing strategic demands. The Navy’s willingness to adapt to “modern trends in warfare” and the need for a more nimble and responsive fleet to counter the omnipresent threat of enemy submarines and aircraft heralded the end of the era of the battleship.