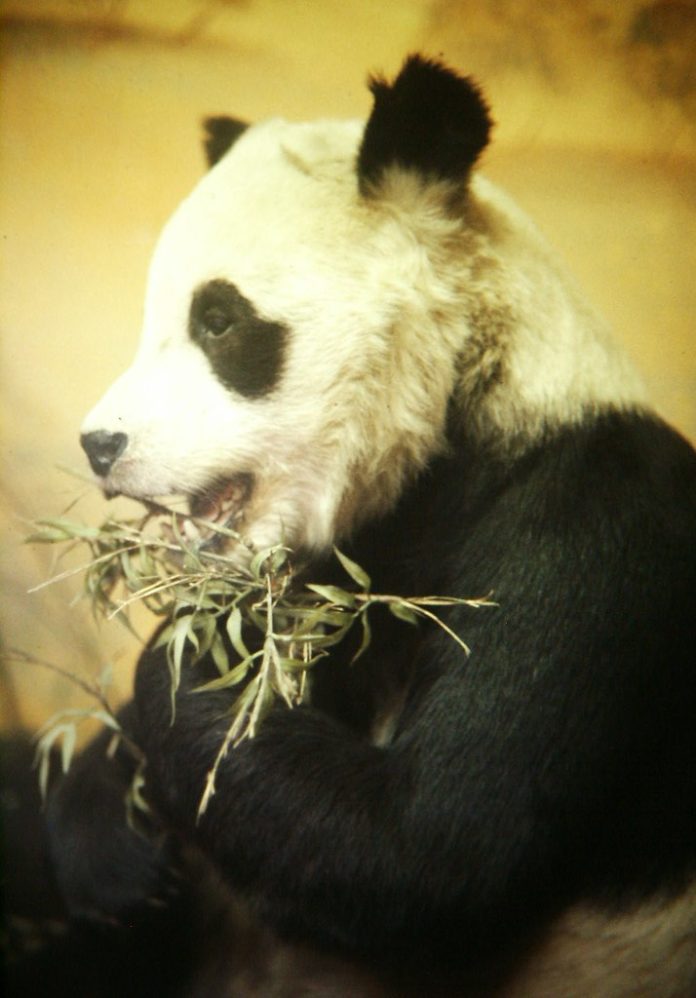

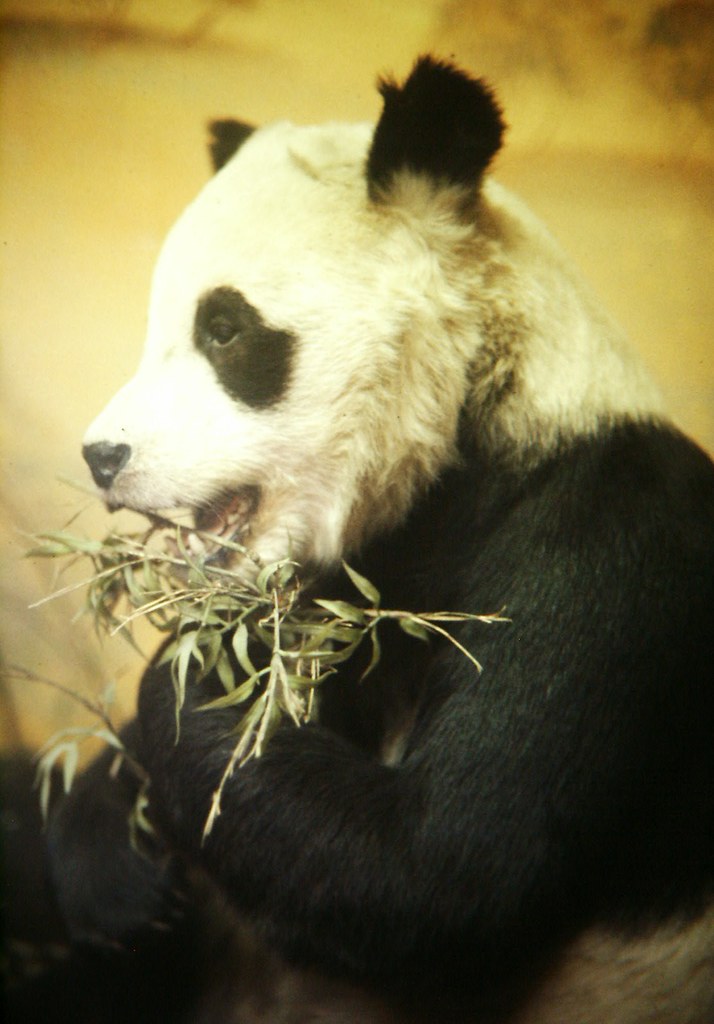

Chi Chi, the giant panda from London Zoo, once made headlines not for her expected dalliance with a male giant panda in Moscow, but for her surprising choice of partner: a zookeeper.

This episode provides a unique window into the complexities of animal behavior, particularly the phenomenon known as sexual imprinting.

Sexual imprinting, a form of phase-sensitive learning, plays a crucial role in the development of an animal’s social and sexual preferences. It is defined by the period in which an animal, at a young stage, learns the characteristics of a desirable mate.

This rapid learning process seems to function independently of the outcomes of the behavior and may occur within a critical time window. For instance, male zebra finches are known to favor mates that resemble the female bird that reared them, a clear example of sexual imprinting.

Sir Thomas More first described the phenomenon in domestic chickens in 1516, in his treatise Utopia. This was 350 years before the amateur biologist Douglas Spalding reported it in the 19th century.

Later, the early ethologist Oskar Heinroth rediscovered it, and his disciple Konrad Lorenz conducted extensive studies and popularized it through his work with greylag geese.

Chi Chi’s experience is an illustrative case of how this process can result in unexpected outcomes when a non-human animal is reared by humans.

The giant panda, which resided at the London Zoo, was taken to Moscow Zoo to mate with a male giant panda named An An.

Contrary to the natural expectation, Chi Chi rejected the male’s advances but, remarkably, made a “full sexual self-presentation to a zookeeper.”

The behavior Chi Chi displayed aligns with the well-documented instances where animals reared by humans develop sexual attraction toward them. Such imprinted animals have their social and mating behaviors inherently influenced by these early experiences.

The anecdote of Chi Chi’s preference over her own species for a human caregiver stands as a testament to the power of imprinting.

Chi Chi’s actions also spark discussion on the broader topic of imprinting across species. This can include imprinting on inanimate objects or even organizational imprints in human settings like computer systems, where users prefer systems similar to the first one they learned on.

Imprinting is a reminder of the delicate balance between nature and nurture in shaping behaviors, extending even to sexual and social preferences.

Interestingly, the concept of imprinting can provide insights into various human psychological phenomena as well. For example, the Westermarck effect, a form of reverse sexual imprinting, occurs when individuals who live in close proximity during early life are desensitized to sexual attraction to each other later in life.

This effect has been observed across different cultures and societies, underscoring the universality of these developmental processes.

Relevant articles:

– Imprinting (psychology)