The strategic landscape of nuclear deterrence is undergoing a significant transformation. This shift marks an unprecedented change in the nuclear age, necessitating a reevaluation of the current force structure and arms control measures. As tensions rise and the global order seems increasingly precarious, the future of nuclear deterrence and arms control appears to be at a critical juncture.

Nuclear deterrence has remained a pivotal aspect of American security policy since the inception of the Cold War. The deterrent’s purpose is simple yet profound: to convince adversaries that any aggressive act would incur unacceptable risks and costs, far outweighing any potential gains. To underscore the credibility of this deterrence, the United States cultivated a robust nuclear force, capable of inflicting severe retaliatory damage.

During the Cold War, the concept of mutual assured destruction (MAD) with the Soviet Union was a cornerstone of strategic stability. It is widely believed that this terrifying equilibrium of potential annihilation deterred the superpowers from engaging in an all-out nuclear confrontation, despite close calls during episodes like the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Berlin Crisis.

In the post-Cold War era, as the United States solidified its network of alliances, the concept of extended deterrence gained prominence. The challenge, however, was making credible the notion that the U.S. would risk nuclear retaliation on its own soil to protect its allies – that an American president would indeed risk Chicago to defend Hamburg.

NATO’s nuclear policy has evolved to address the rising complexities of modern threats. At the heart of NATO’s deterrence and defense posture lies a mix of nuclear, conventional, and missile defense capabilities, augmented by cyber and space assets. The Alliance continues to emphasize the critical role of nuclear deterrence in preserving peace and preventing aggression. At the 2023 Vilnius Summit, NATO leaders reaffirmed their commitment to ensuring the credibility and effectiveness of their nuclear deterrent mission and stressed the importance of strengthening the integration of capabilities across all domains.

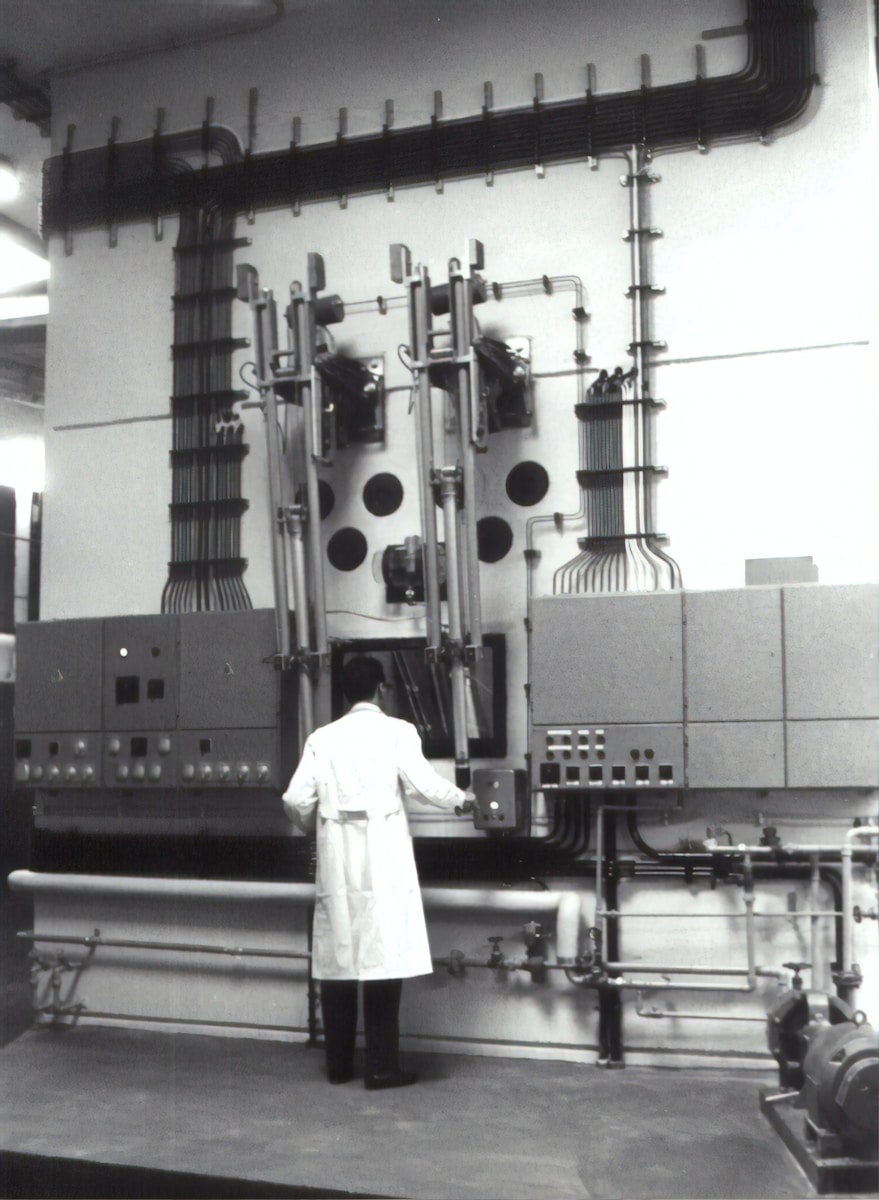

Meanwhile, advancements in space-based early warning systems, such as those in the Defense Support Program, illustrate the continuous enhancement of deterrence infrastructure. These satellites play a pivotal role in detecting missile launches, thereby contributing to the broader framework of deterrence by providing vital warning information to defense agencies.

The current global security environment, however, is characterized by strategic competition and an increased emphasis on nuclear weapons. Russia’s modernization and expansion of its nuclear arsenal, combined with its nuclear saber-rattling over Ukraine, highlight the persistent challenge to regional deterrence.

Despite the reduction of nuclear weapons since the Cold War’s peak, the latest incursions, such as Russia’s actions in Ukraine, have led NATO to commit to strengthening its long-term deterrence posture against chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear threats.

The intricate challenge of maintaining nuclear deterrence in this evolving landscape calls for a careful reexamination of force requirements. The United States may need to go beyond the 1,550 warheads limit set by New START, with considerations for new delivery systems like a nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile.

Arms control, a long-standing component of strategic stability, now faces a complex future. The suspension of Russian compliance with the New START agreement poses profound questions about the future utility of stability dialogues and risk-reduction measures. While these tools could assist in decreasing the likelihood of nuclear conflict, the prospects of engaging in treaties or agreements that restrict nuclear capabilities appear slim.

The strategic calculus for nuclear deterrence and arms control has reached a defining moment. The urgency to adapt its nuclear posture and pursue pragmatic arms control measures has never been greater.

Relevant articles:

– U.S. Nuclear and Extended Deterrence: Considerations and Challenges, brookings.edu

– NATO’s nuclear deterrence policy and forces, NATO.int

– Special Report: 21st Century Nuclear Deterrence, U.S. Department of Defense (.gov)

– Requirements for nuclear deterrence and arms control in a two-nuclear-peer environment, Atlantic Council