Beyond the visible horizon where naval strategy unfolds, the United States Navy grapples with a pressing dilemma: the depletion of its Tomahawk missile stockpile at an unsustainable rate. Since initial retaliatory strikes began on January 11 against Iran-backed rebels in Yemen, Navy ships have repeatedly employed both carrier-launched aircraft and sea-launched Tomahawk cruise missiles to strike Houthi radar,drone,and anti-ship missile site. These precision strikes have strained the Navy’s arsenal, as current replacement rates fail to keep pace with consumption.

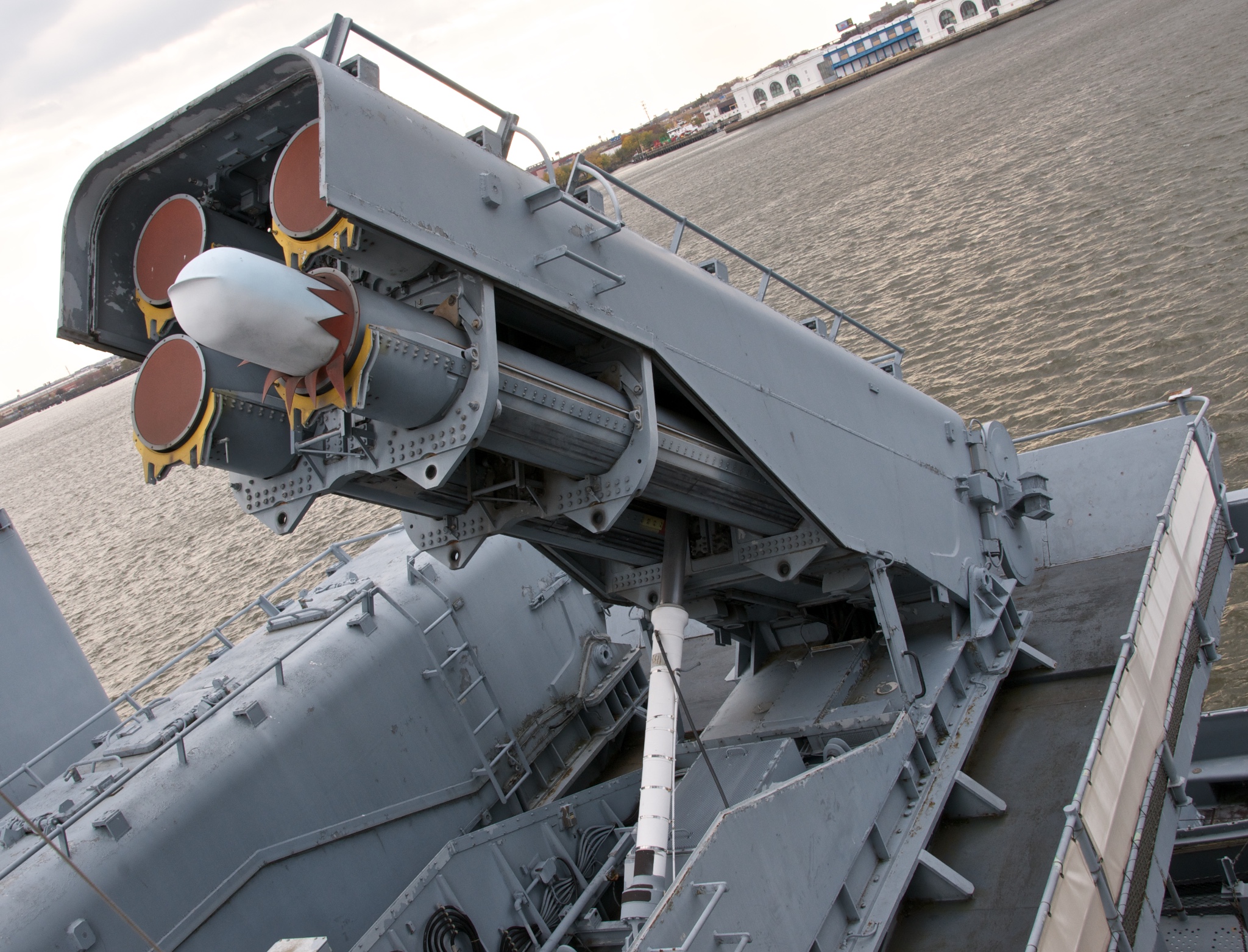

The Tomahawk has long been the Navy’s weapon of choice for deep strike missions, offering a combination of range, precision, and lethality without exposing aviators to risk. Its versatility was proven yet again in the recent operations against Houthi radar, drone, and anti-ship missile sites. “Opening day strikes alone expended more than 80 Tomahawks to hit 30 targets within Yemen,” the Navy reports.

The ramifications of this expenditure pattern are far-reaching. Last year’s entire Tomahawk purchase of 55 missiles accounted for 68 percent of the precision munitions fired at the Houthis in one day. The 2017 and 2018 strikes in Syria saw a similar pattern, with 59 and 66 Tomahawks launched respectively, the Navy bought just 100 Tomahawks in 2018 and then zero Tomahawks in 2019-failing to offset the expenditure rate of the Syria strikes.

The Navy’s spending of $2.8 billion in the past decade for 1,234 missiles seems robust until one considers the needs of a global force with over 140 ships and submarines capable of firing Tomahawks. This amounts to an average of just 8.8 new missiles per ship, a fraction of what might be necessary in a full-scale conflict.

Furthermore, the 2024 budget reveals the Navy’s intent to acquire zero new land-attack Tomahawks, opting instead to modify existing ones into Maritime Strike Tomahawk variants. Compounding this issue are the challenges of surging production to meet heightened demand, evidenced by fluctuations in purchases leading to instability in the industrial base and consequent bottlenecks in components such as rocket motors.

Given the two-year lead time to build a new Tomahawk and the projected delivery rate of just five missiles per month starting in January 2025. The historical context amplifies these concerns; during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, approximately 800 Tomahawks were deployed—a number that would take a decade to replenish at today’s production rates.

The Senate’s version of the national security supplemental has earmarked $2.4 billion to recoup combat expenditures in the Red Sea, its division across various operations means that it may not resolve the Tomahawk shortfall. An additional $133 million in the bill for cruise missile rocket motors is a welcome investment for relieving bottlenecks, Congress should also force the Navy to procure a steady quantity of the missile for years to come.

related images you might be interested.