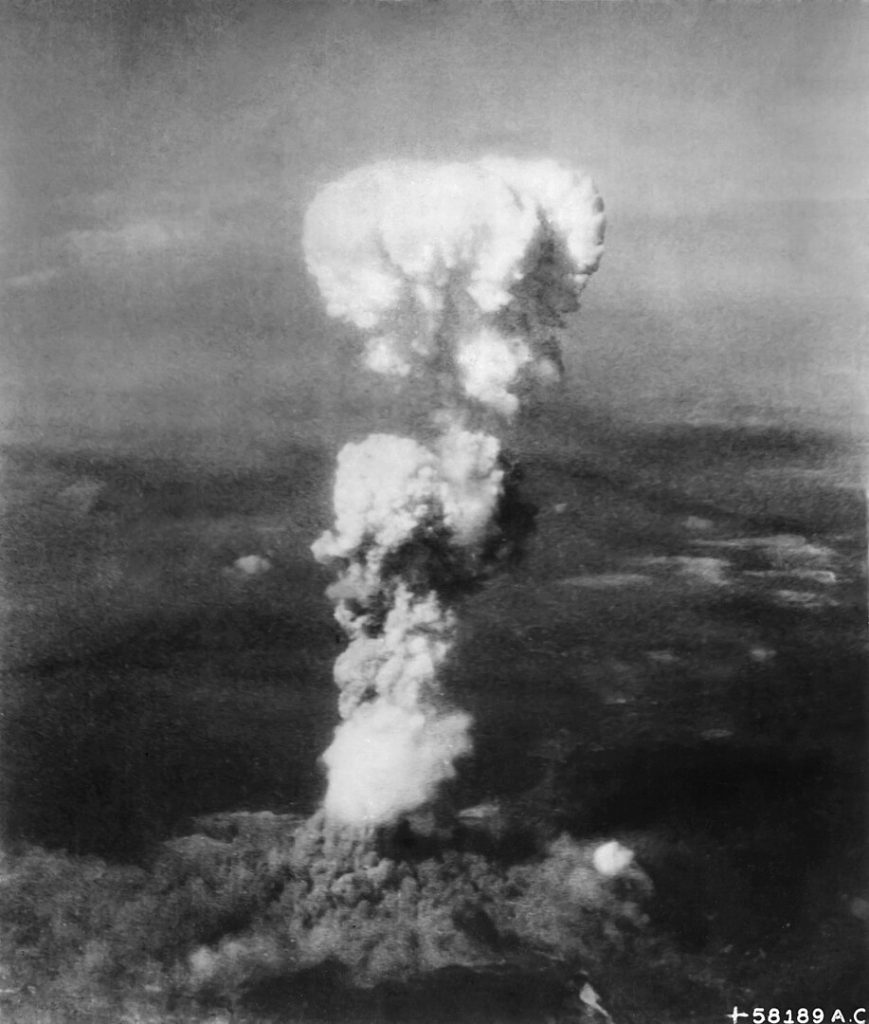

The conclusion of World War II was marked by a harrowing decision that changed the course of history: the dropping of two atomic bombs on Japan. However, a lesser-known fact remains that a third atomic bomb, potentially bound for another Japanese city, lurked in the shadows of the Manhattan Project’s endgame. The discussion of this third bomb’s intended target revives the haunting narratives of atomic warfare and reflects a time when the world stood on the precipice of nuclear annihilation.

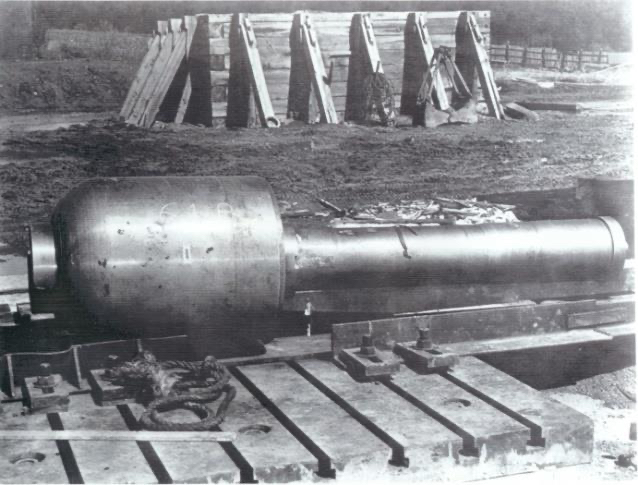

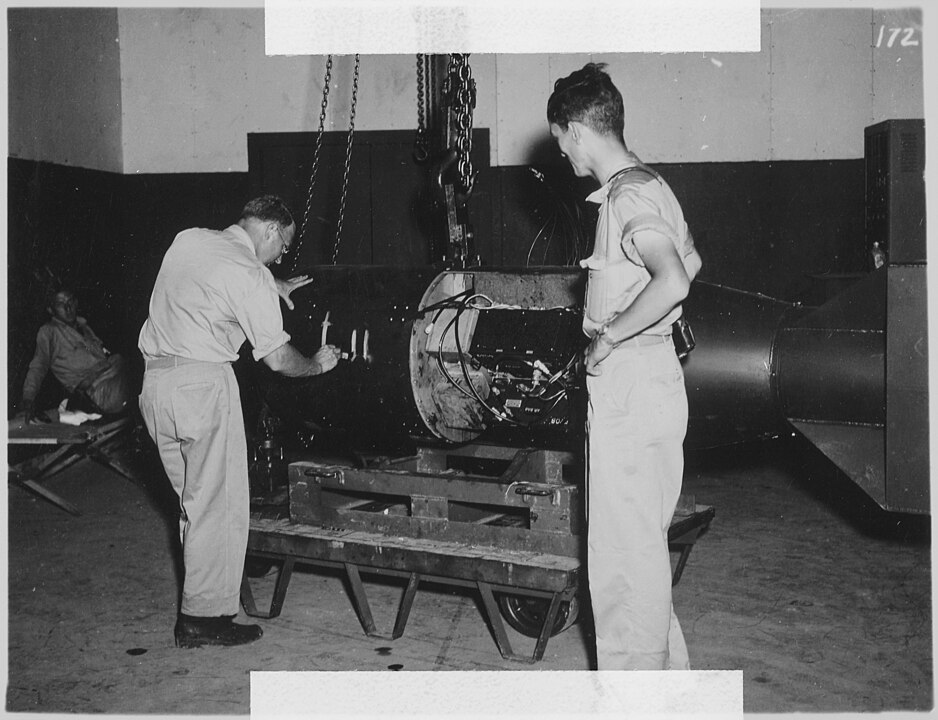

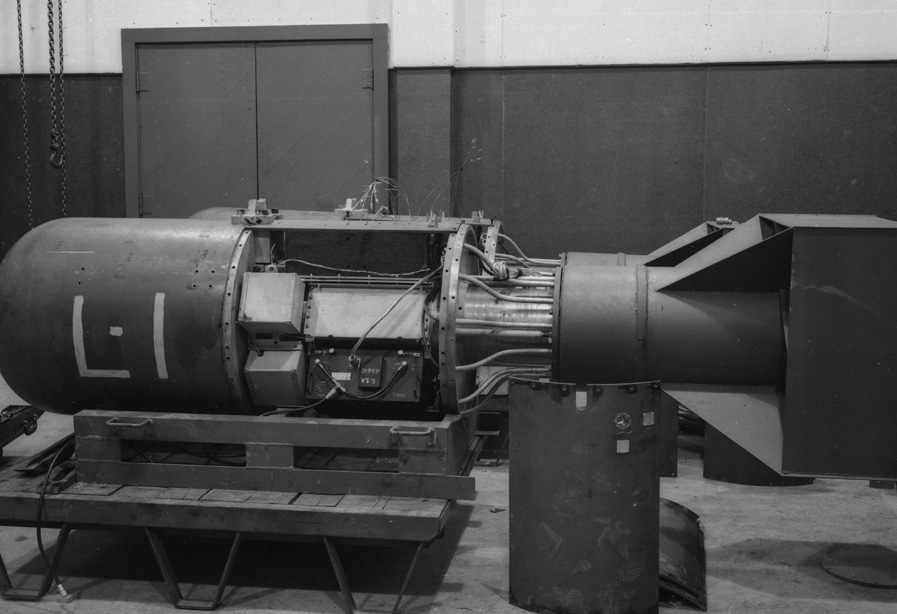

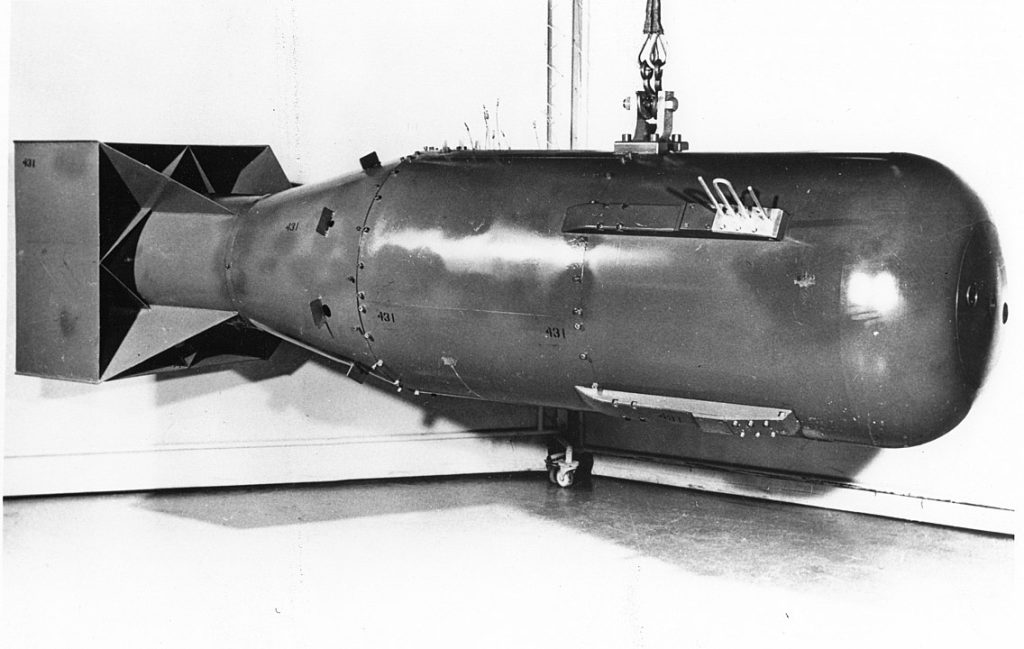

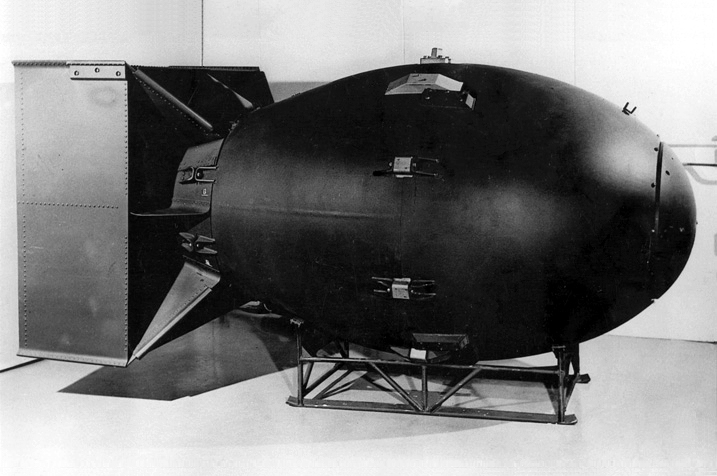

The Manhattan Project, an unprecedented secret endeavor that involved the United States rushing to develop the world’s first atomic weapons, culminated in the nuclear age’s dawn. It involved three primary locations across the country: Hanford, Washington; Los Alamos, New Mexico; and Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The project’s success led to the deployment of the first two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare: “Little Boy,” dropped on Hiroshima, and “Fat Man,” detonated over Nagasaki.

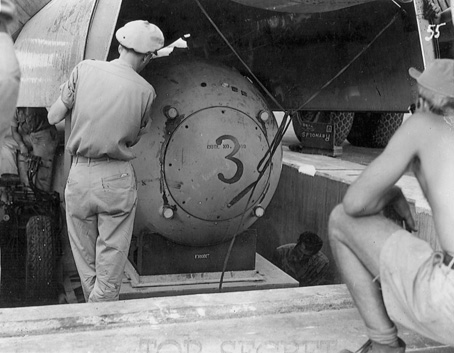

But the threads of history could have woven a different pattern. As revealed, a third bomb was in assembly, with the plutonium core that later became infamous as the “demon core” ready for a “third shot” against Japan in late August 1945. The halt in its assembly came with Japan’s surrender following the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the shocking declaration of war by the Soviet Union, once bound by the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact.

The existence of a third bomb invites us to examine what could have been. Speculation swirls around the undisclosed location this third weapon would have targeted, opening discussions on the potential impacts and the further loss of life that might have ensued. The Manhattan Project’s outcome was already of such magnitude that ethical and moral questions arose among those who understood its intent, and these considerations weigh heavily when contemplating the deployment of yet another bomb.

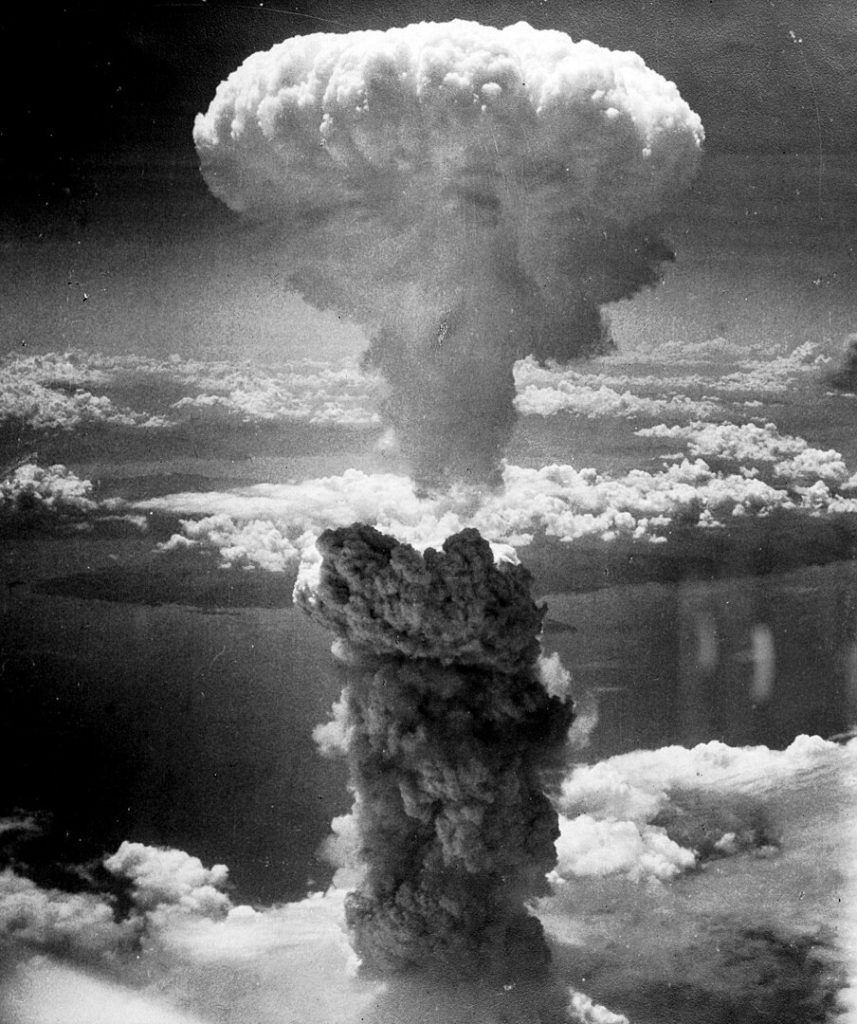

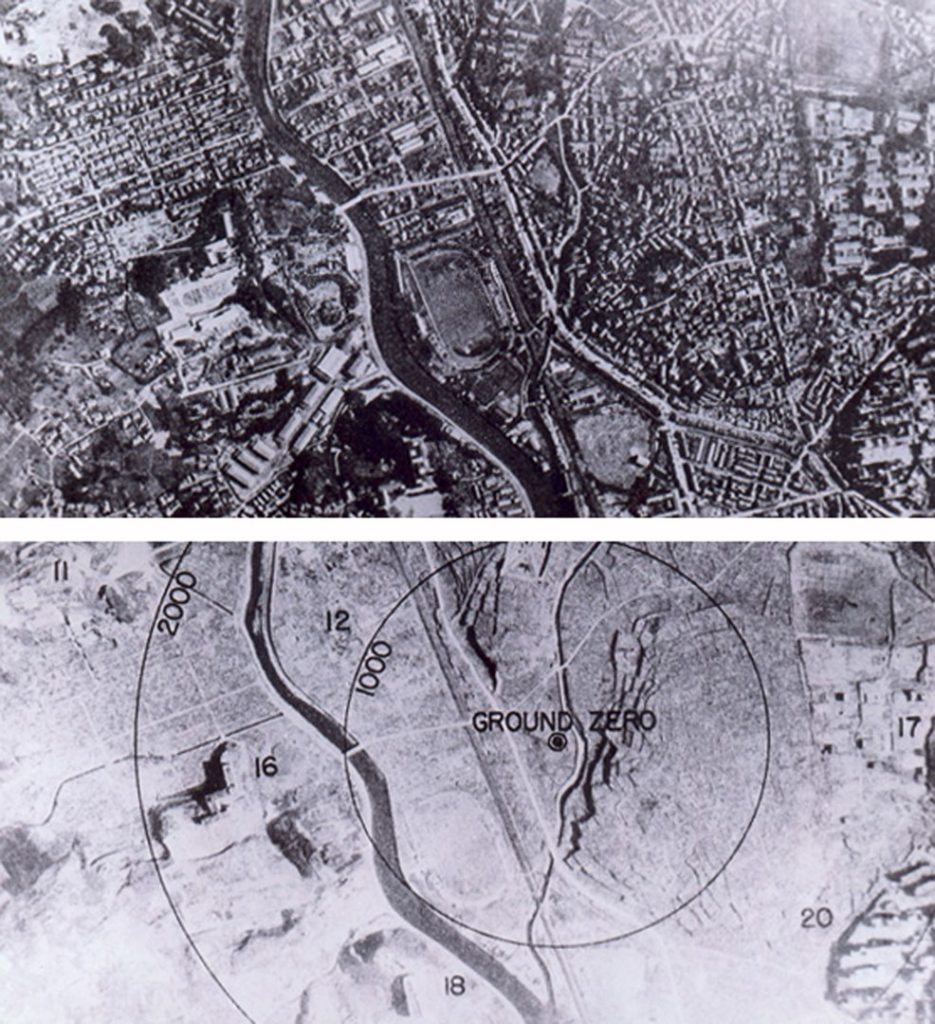

The “Fat Man” bomb’s delivery over Nagasaki on August 9, 1945, marked a tragic chapter in world history. Built by scientists and engineers at Los Alamos Laboratory using plutonium from the Hanford Site, it was dropped from the B-29 Superfortress Bockscar, piloted by Major Charles Sweeney. The bomb’s detonation led to the fission of about 1 kilogram (2.2 lb) of the 6.19 kilograms (13.6 lb) of plutonium in the pit, releasing the energy equivalent to the detonation of 21 kilotons of TNT.

After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the demon core—destined for the third bomb—found its fate redirected towards tragic experiments rather than wartime use. Within a year of Japan’s surrender, two physicists fell victim to radiation exposure from the demon core, leading to their untimely deaths and the halting of criticality experiments at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Eventually, the core was deemed too radioactive for its intended purpose and was melted down, its material recycled into new warheads.

The unspent third bomb, a grim specter of what could have extended the catalogue of horror, leaves behind a legacy that is still dissected and understood today. Through the lens of this atomic trinity—the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the third that never was—we are reminded of the era’s scientific leaps and the profound ethical quandaries they posed. The Manhattan Project, while a significant chapter in American history, continues to evoke questions that echo through the years, reminding us of the power and peril held in the hands of those who dare to split the atom.

related images you might be interested.