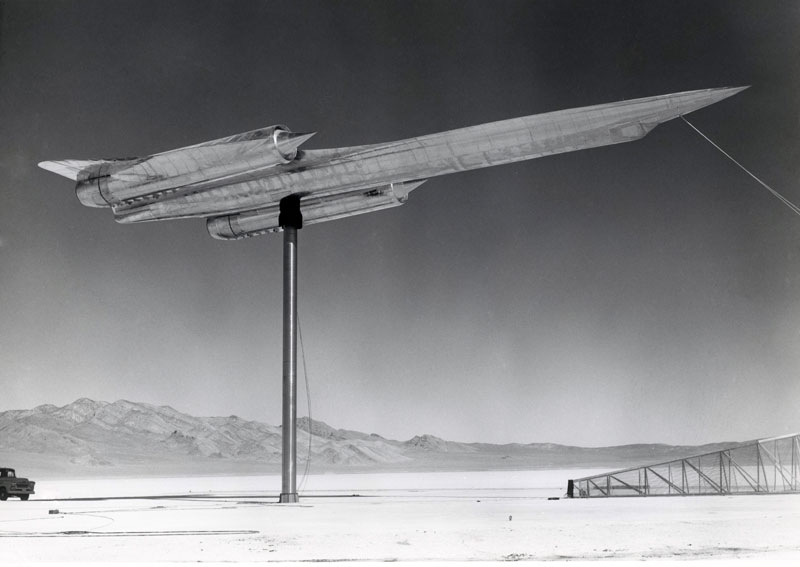

On a clear spring day in 1962, Louis Schalk, a test pilot for Lockheed Aircraft Corp., took to the skies in an aircraft that would forever alter the landscape of reconnaissance aviation. The A-12 OXCART, a successor to the venerable U-2 spy plane, was a sight to behold with its massive engines, strikingly sharp nose, and swept-back wings. Designed to fly at thrice the speed of sound and at altitudes exceeding 90,000 feet, this marvel of engineering was a testament to the ingenuity and ambition of its creators.

The A-12’s development, a closely guarded secret, was spurred by the realization that the U-2’s days were numbered in the face of improving Soviet air defenses. As the U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers learned on May 1, 1960, being detected and subsequently shot down over Sverdlovsk, the risk to pilots and the need for a more elusive aircraft was all too clear. The quest for invisibility led to the innovation of radar-absorbing materials, and the A-12 aimed for a trifecta of speed, altitude, and stealth to evade detection.

Lockheed’s team, led by the legendary Clarence “Kelly” Johnson, encountered numerous technical challenges while striving to meet the demanding specifications. From machining titanium—a metal chosen for its high-temperature endurance—to developing special lubricants and fuels, each obstacle was methodically overcome. By 1965, after an arduous and risky series of tests, the A-12 reached operational status and achieved record-breaking speeds and altitudes, including a sustained Mach 3.2 at 90,000 feet. Despite this, the A-12’s moment in the operational spotlight was brief; it flew only during the BLACK SHIELD operation over East Asia from May 1967 to May 1968.

The rapid evolution of reconnaissance technology meant that the A-12, as incredible as it was, soon found itself superseded. The development of imaging satellites, such as CORONA, and the introduction of the SR-71—another brainchild of Lockheed, which bore strong family resemblance to the A-12—heralded a new era. While CORONA lacked the timely, high-resolution imagery of the A-12, it was beyond the reach of anti-aircraft missiles and political provocations. With the SR-71 ready to take the stage and the diminishing returns of maintaining a covert aircraft fleet, President Johnson decreed the retirement of the A-12 in 1968.

The Oxcart program spanned over a decade, starting in 1957 and concluding in 1968. Lockheed manufactured fifteen Oxcarts, three YF-12As, and thirty-one SR-71s. These forty-nine supersonic aircraft completed 7,300 flights, accumulating 17,000 airborne hours, with over 2,400 hours above Mach 3. Unfortunately, five Oxcarts were lost in accidents, resulting in two pilot fatalities and two narrow escapes. Additionally, two F-101 chase planes were lost, along with their Air Force pilots during the test phase of Oxcart.

The primary goal of the program, to develop a reconnaissance aircraft with unprecedented speed, range, and altitude capabilities, was successfully achieved. Noteworthy advancements in aerodynamic design, engine performance, cameras, electronic countermeasures, pilot life-support systems, antiair devices, as well as the milling, machining, and shaping of titanium, emerged as significant by-products of the endeavor.

related images you might be interested.